The Power of Smiling in Greensburg, PA

How You Can Benefit From Smiling

Have you ever fake-laughed long enough to find yourself laughing for real, never quite sure when you made the transition or why? Have you ever smiled, even at something in passing, and immediately felt better?

When I’m sad, I hunch my shoulders. When I’m happy, my body and face open like a flower in bloom. When I’m uncomfortable, I cross my arms or my legs. You can tell a lot about someone’s emotions just by looking at their body; that’s how powerful the motions behind our emotion are. We know that our emotion affects our motions, but what if it worked the other way around?

What if all we had to do to be happier was just smile?

Here’s the thing: we can. It really is that simple.

“Smiling stimulates our brain’s reward mechanisms in a way that even chocolate…cannot match,” write Michael Sinclair and Josie Seydel in Working with Mindfulness.

That’s powerful.

Today, I’d like to take you through the research and show you, prove to you, how smiling can make a dramatic difference in your life.

First, let me crack a quick smile. You’re welcome to join me with a brilliant smile of your own.

If smiling can truly make us happier, we might as well start practicing, right?

Smiling Affects Your Brain

Sitting in a plain room, subjects are asked to make long “eee” and “uuu” sounds while psychologists look on and take notes. A strange experiment, but one that makes you use different facial muscles to make different noises. One by one, the subjects complete the experiment. The psychologists find that those asked to pronounce “eee” felt better, they were happier, than those asked to say “uuu.” Which facial muscles you use does make a difference, they conclude.

The research in this area of science is heavy, but not without controversy and plenty of disagreement.

The roots of the science are also old. In a 1989 journal article, psychologists Pamela Adelmann and Robert Zajonc trace it all the way back to the late 19th century. In 1865, a scientist by the name of Pierre Gratiolet wrote, “The movements and bodily attitudes, even if they arise from fortuitous causes, evoke correlated sentiments.” Others would go on to publish similar theories, like William James in 1884, who would be the one to set off a torrent of research in the next century, both for and against his controversial belief.

What does modern science say, though?

In 1982, Swedish professor Ulf Dimberg published results from a study in which he showed subjects photographs of happy and angry people. He measured their heart rate and skin conductance responses (which has to do with the amount of electricity your skin conducts under different stimuli). If the subject was shown a picture of a happy person, they became happy; if they saw the photo of an angry person, that was the emotion they adopted. Crazy, right?

Gerald Cupchik and Howard Leventhal, in 1974, asked patients in a study to spontaneously smile and laugh at cartoons playing on a television in front of them. They found that canned laughter was correlated with funnier ratings when the patients rated the cartoons on funniness after the experiment (although, interestingly enough, the results were stronger for women and weaker for men).

There’s an interesting study cited in a 1989 New York Times article, conducted by a team of researchers from Clark University, in Massachusetts. Without telling them why, they gave instructions like, “raise your eyebrows” or “open your eyes wide.” Each of these instructions was based on the idea that certain facial movements are associated with certain emotions, and what they found was that when their subjects made those facial movements they adopted the associated mood.

How can this be? How can something as simple as a fake smile make us happier?

Scientists have published just as many papers trying to explain that, as it turns out (I exaggerate only a little).

Priming is a concept in psychology that suggests that because of how our brain associates different concepts together, certain stimuli bring out specific responses. For example, if I say the word red and ask you to think of a fruit, you’re likelier to think of apples or cherries than oranges and bananas. The word “red” primes you to think of concepts related to the color, so when I follow with fruit it’s natural for you to think of red fruits first, before thinking of fruits of any other color. Interesting stuff, right?

What if the magic of smiling worked the same way?

In 1968, Robert Zajonc theorized that how often we’ve been exposed to a stimulus will affect our reaction to it. If the stimulus is new, we’re prone to experience it negatively. That is, if we know to associate the stimulus with something good, then we are more likely to react positively to it.

What if we’re so used to smiling when he have good reason to that when we fake smile it brings back the feeling of those experiences?

What if our mind is accepting our body’s interpretation of the stimuli subconsciously or without thinking? When you fake smile, maybe the mind thinks you’re smiling for a reason and reacts the way it would if you truly were.

There may be a more specific answer, as well. Robert Zajonc, whose name we’ve heard a lot so far and who we can safely conclude to be a leader in this area of research, came up a theory that says that use of our facial muscles can impact the temperature in our body. He stated that when, for example, we smile, the muscles on our cheek tighten and it decreases the flood of blood to our sinus, cooling it as it flows into the brain. The change in temperature can have a significant effect, because the hypothalamus — which helps determine emotion — is sensitive to temperature.

The science is still there to be debated and we may find neither of these explanations to be adequate. Nevertheless, what matters the most still stands…

…if you want to be happier one easy way to get started is to just smile.

Not All Smiles Are Made Equally

In 2014, three scientists decided to be contrarian and published a paper called, “Not Always the Best Medicine: Why Frequent Smiling Can Reduce Wellbeing.”

As it turns out, people don’t just smile when they’re happy, sometimes they smile when they’re unhappy too. They conducted a test to see whether this changed the story as far as how smiling can help us become happier. They grouped people two ways: those who believe that smiling reflects happiness (reactive) or whether it pursues happiness (proactive). That is, whether you have to be happy to smile or smile to be happy.

The results were spectacular: if you believe that you have to be happy to smile, you are less likely to become happy by smiling more frequently. You can, in fact, become less happy.

This wasn’t the first time the more positive conclusions of the debate have been contradicted. In 1982, scientists by the name of Kleinke and Walton ran an experiment to see if they too could find a relationship between smiling and feeling better, but they found no correlation between the two at all. Their subjects were not feeling happier after smiling.

What’s going on? Why are different tests reporting different results?

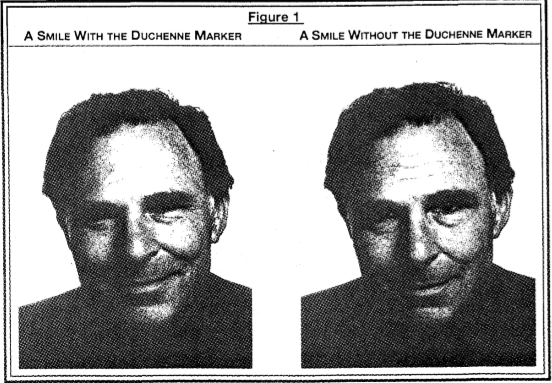

We smile differently when we smile for different reasons, as was discovered over 150 years ago by a French neurologist named G.B. Duchenne.

Scientists have developed the concept of the ‘Duchenne marker’ since then. The marker tells them whether the smile is associated with a positive or negative reaction.

As recounted in a 1996 brief by Mark Frank and Paul Ekman, happy smiles move specific muscles — the pars lateralis. That’s the area near our eye, the area that we tend to constrict when we’re happy, as if our eyes were squinting. It’s that squint that they refer to as the Duchenne Marker.

Paul Ekman is known to argue that because we smile in different ways, it’s natural to see contradictory results when researchers run experiments about smiling and happiness, that is if they don’t control for how the subject is smiling. In 1988, when Ekman — along with Frisen and O’Sullivan — controlled for the Duchenne smile, they found that their results were as expected. The right kind of smile correlates with positive emotions.

The moral of the story: if you’re going to smile, smile for true.

Want to know a trick? Think of something you experienced that was funny or that made you happy, and I assure you that if you try you’ll smile from ear to ear.

What Does the Power of Smiling Have to Do with Dentistry?

There are many studies that link dental health problems with symptoms related to unhappiness. Tooth loss, for example, is associated with depression and anxiety. Stress and depression were found to be related to periodontal (gum) disease. Researchers have even found unhappiness to be related to the frequency that one goes to the dentist.

It could be that causation runs the other way. Meaning, maybe those with depression, stress, and anxiety are simply less likely to take care of their teeth.

With most things, it’s probable that causality runs both ways. Much like how both our emotions determine motions and how our motions determine emotions, it’s possible that dental problems are both caused by and cause emotional health issues.

I’ve been practicing in Greensburg for over 30 years and the emotion that I’ve had the privilege of experience in my patients after a procedure is both amazing and remarkable. Imagine having been ashamed to smile — so that even if you were actually happy, you were still afraid to smile —, imagine the toll this can take on someone. What if you could smile again without being embarrassed?

The smile is such a powerful component to the human body. It has driven hundreds of researchers to debate how it affects our wellbeing and there are so many lines to this research, it all speaks to the profound influence our mouth has on us. I truly do believe that taking care of your oral health, including cosmetically, is key to living a joyous life.

Of course, many people have been able to lead happy lives, even with missing teeth, tooth decay, and gum disease. They find other ways to be happy. This day in age, though, with affordable dentistry at your fingertips, why walk down that road? Wouldn’t you rather have a smile you’d be proud to flaunt?